Engineering TESLA, a Futurist Radio-on-Stage

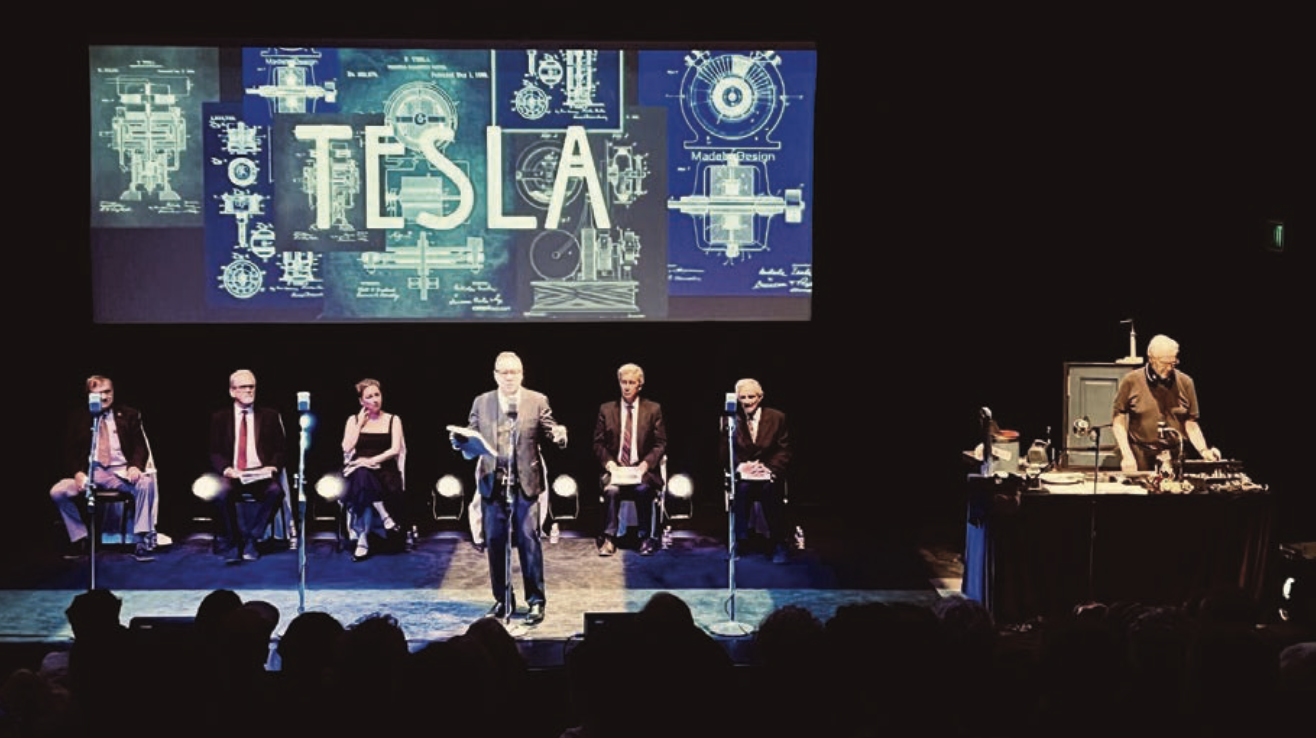

The cast of TESLA, from left to right: Dan Lauria, Gregory Harrison, Vanessa Stewart, French Stewart (standing), Charles Shaughnessy, and Hal Linden, with Tony Palermo on sound effects.

“When wireless is perfectly applied the whole earth will be converted into a huge brain, which in fact it is, all things being particles of a real and rhythmic whole. We shall be able to communicate . . . as though we were face to face, despite intervening distances of thousands of miles, and the instruments through which we shall be able to do all of this will fit in our vest pockets.”

This writing sample dates back to 1927, the year television saw its very first broadcast. Learning that Nikola Tesla foresaw not only the internet, but even the iPhone, left me positively floored. Even as a physics major and eager student of the history of science, I previously knew little of the man himself, let alone the extent of his grit and hardship. Where better to have witnessed the Tesla story, portrayed in all its humanity, than at last month’s TESLA: A Radio Play for the Stage.

Written by Dan Duling, directed by Michael Arabian, and performed from Oct. 4 through Oct. 6 at Ramo Auditorium, TESLA was one piece among several in Caltech’s Opening Doors series. This multidisciplinary series, a blend of dance, music, and theater events, was held in turn as part of the ongoing *PST ART: Art & Science Collide* initiative led by the Getty to promote the intersection of arts and sciences.

A vivid exploration of Tesla, his genius, and his struggles, the play takes a panoramic view of its mystifying title subject. Woven into the narrative are Tesla’s early career at Westinghouse Electric Corporation, his spats with Edison amidst the war of the currents at the turn of the 20th century, and the man’s tragic final years spent in poverty and anonymity with only his beloved pigeons for company.

The concept for TESLA had long percolated in the mind of writer Dan Duling, as he has been spellbound by the inventor for decades. “I was encouraged to look at Tesla material all the way back in 1990. Quickly I became intrigued with his history, all sorts of tantalizing things like: How could someone as famous as Thomas Edison in 1900 virtually end up unknown?” In unraveling such questions, Duling’s writing process entailed the endless exploration of Tesla’s own writings. Paying particular attention to how the man articulated himself proved crucial to the integrity of the play’s portrait of him. Lest, as Duling put it, TESLA in its representation of the man “violat[e] the fidelity to his life and his mind.”

“And the more I got into it,” Duling added, “the more I began to become fascinated by the politics of it, the economics of it, the capitalist challenges of it, and also just the fact that he was so clearly a brilliant mind with so much to offer the world.” There was no limit to the fascination the figure inspired in Duling, especially as his research made the scale of Tesla’s clairvoyance all the clearer. “He was a futurist in the purest sense,” in the playwright’s words.

The war of the currents, having squared futurist against futurist, was likely Duling’s favorite part of the history to adapt. “It was wonderful to have that battle between Edison and Tesla kind of as the centerpiece of the play. Tesla was always seeing the greater possibility: the larger picture of what might be possible.” In the process, Duling’s view of Edison—who received much more, and largely flattering cultural coverage than his opponent—also changed in his mind, namely for the worse.

“Two things really informed my attitude about Edison,” Duling explained. “One was seeing the view of him actually arranging the execution of an elephant, which is as horrific a moment as I can imagine. And, historically, becoming aware of Edison’s desire to have absolute monopoly [in both filmmaking and electricity]. … I’m always prone to being on the side of the underdog, but in the case of Edison and Tesla, it became much more personal.” Indeed, the two in their approaches to capitalism were chasmically different: one, a ruthless monopolist; the other, an awkward researcher who nearly never left his lab. “If you just looked at it from Tesla’s point of view, business was just an unfortunate necessity. … His confrontation with American capitalism was his greatest Achilles heel.”

And it was this lack of ruthlessness that laid the foundation for his heartbreaking later years. Duling made clear, however, how much his script steered away from emphasizing that period. “This wasn’t a play about that last chapter in his life. All you need to know is that his ability to do what he set out to do had been effectively taken away from him. All he’s left with are compulsions, and obsessions, and greater attempts to make more outlandish statements in hopes of someone listening and funding something. Anything that could keep him afloat.”

With a finished stageplay, TESLA was first performed in 2013 for a reading in a co-production with Caltech and the Pasadena Playhouse. “It was only for one reading, and we completely sold out that theater,” shared Arabian. “We were really excited that there was so much interest in Tesla at that time. So few people even owned Tesla cars.” The play was then greenlit for a one-weekend showcase at the Laguna Playhouse in 2017, featuring a team of professional actors in contrast to the original show’s amateur cast. “And then Michael Alexander [Caltech’s Campus Arts and Culture Liaison] told us to do it for the PST festival. It was amazing that the actors who did it seven years ago at the Laguna Playhouse were all available to do this production.”

Only French Stewart, who had the honor of portraying Tesla, was present for that first show. His prior project Stoneface: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Buster Keaton, a play about the titular comedy legend, practically molded him for it. “It’s a similar story. He’s this genius and everybody loves him, but he’s not a good businessman,” Stewart said, likening Charlie Chaplin to J. P. Morgan. “It’s a very human story. And there must be something in the zeitgeist because it’s the exact same story.”

Asked about that something in the zeitgeist, Stewart spoke to the national identity imbued in the sort of narrative Keaton and Tesla share. “I’m sure it’s worldwide, but to me, it’s a very American story—a squeaky-wheel-gets-the-grease kind of thing. Some people are just not easily able to sell themselves: even if they’re really good, they get buried. And some people aren’t wired that way. It’s sort of a strange artistic and scientific natural selection.”

Rather than stress about pitch-perfect historical accuracy, Stewart focused on channeling the soul of his character. “For me, I try to get a sense of who the person is, and not worry about mimicking them. I try just to capture the essence of who they seem to be from my research on them, and put that forth. Maybe for a movie you’d get deeper into the look, but the important thing for me was just trying to create the spirit of him.”

That spirit, according to the actor? “I think it’s unwavering artistic vision. And science was his art, and he says it in the play: he can’t turn off his brain. He’s incapable of it. There may be things that entertain his brain, like poker or friendship or pigeons, but it’s an unending search.”

Following those early shows, the play wasn’t to return to Caltech without monumental change. True to its namesake’s legacy, TESLA was reinvented as a radio play for the stage. “I didn’t want it just to be a reading,” Arabian said in explaining his vision. “I wanted to do some staging, lighting, projections. The sound effects is always part of any radio play, but it’s always nice for the audience to see the special effects live—that also makes it very theatrical.” With limited time before Opening Doors, this was an ambitious endeavor. “In our three days’ rehearsal, we squeezed in a lot of elements.”

All the better the show could rely on the talents of sound effects artist Tony Palermo, a veteran of L.A. radio. “I get about 200 to 300 productions of my plays around the world every year,” Palermo nonchalantly told me. “The challenge with this particular show—because it was very screenplay-y—is that there were many short scenes. And many characters. … It’s like a movie happening in real time on stage.”

Intelligibly rendering 47 characters, with only a handful of actual humans on stage, was no small feat. “Clarity is everything in radio drama,” as Palermo put it. “You have six actors and all of these different characters. How do we know: Now he’s Edison. Now he’s Mark Twain. Now he’s Westinghouse. Those things were a challenge. It took us several days to figure out: Okay, put this guy at mic #4. Put this guy at mic #1 because he’s playing a different character.” The rest of Palermo’s role proved more straightforward. (“And then there were the sound effects,” he said, almost offhandedly. “That was an easier part, I guess.”)

The radio-on-stage format did present Stewart with some unique acting difficulties. “When you’re constantly on-book and having to refer to it, it gets a little bit tricky. So it was rudimentary body things: standing that long, that sort of thing. Other than that, it was sort of the same type of thing that I’d normally be doing. Being on a stage and trying to keep it entertaining and moving and engaged.”

Somewhere between a straightforward reading and a full production, the medium lends itself well to inexpensive spectacle. “Radio-on-stage is a cheap way to do magic,” Tony added. “It’s the defiance of fakery that bursts through.” In the playwright’s opinion, whatever additional work that defiance demanded of the audience only enhanced their theatrical experience. “[Arabian] insisted who was talking and that sort of thing, but I determined that if the audience had to play catch-up, that was a good thing. Because ultimately, when they were into Tesla’s dilemmas and ambitions, it would only get more compelling.”

And even if some details of the radio-on-stage action were lost on the viewers, the dramatic big picture never was. “Certainly the performances are able to show at least the broader gestures of who’s who and what’s going on and when,” Duling said. The director also incorporated ancillary visual elements to further reinforce the context of a given scene. “We did have [Arabian]’s edition of slides and dates wherever I could without feeling like I was making it mechanical or wooden,” Duling added.

Even with Arabian’s dynamic vision and Palermo’s acoustic embellishments, TESLA remains a feat of minimalistic storytelling. “It’s like a bunch of people being in a cave,” as Stewart imagined it. In this theatergoer’s opinion, TESLA’s simple apparatus—an elevated stage reading with sound effects and basic visuals—underscores the moral at the show’s heart. “If you don’t pay the same attention to the business part of [showbusiness] as you do the show, you won’t be able to do the show,” as Palermo put it. “And Tesla never realized that. And nobody could tell him.”

Capitalism is a cruel, but omnipresent mistress. Whether in theater or science, there is no escaping showbiz.

TESLA: A Radio Play for the Stage concluded its most recent Caltech run on Oct. 6 and was afterward presented at the Big Bear Lake Performing Arts Center from Oct. 10 through Oct. 13.