The Metaphysical Ideas of Plato: Reality or Imagination

I promised you Plato, and here we are. I would say that, after a period of rest where we fantasized about the future and especially about what we should and could have done during the following term, the philosopher I am going to write about fits perfectly. A Mediterranean illumination that I had trying to understand how to find a connection, but it allows us to see the world of Platonic ideas as a parallel reality truly capable of transforming the simple idea of thought, with the intellectual search for being. Mamma mia! What big words—well, let’s delve into the connections that can be seen between the world of science and research with Plato.

First of all, I asked my high school philosophy teacher what was the best approach to writing about the world of ideas. He replied that it is a bit like a black hole (dear astrophysicists) that envelops you, you fall in… And then you no longer know anything and you are in a loop of continuous contradictions. Let’s simplify a bit—let’s get to the essence. Everyone, starting as Platonists, believes that Plato truly founded philosophy and that its metaphorical reality is nothing but the imagination and potential of man. Then, studying Aristotle (in the next edition) they discovered that the Athenian (Athens 428/427 BC – Athens 347 BC) was a bit in the clouds and became Aristotelians, believing more in a material reality than metaphysics. However, I think that it is right to give a correct perspective to Plato who not only wrote the whole life of his teacher (Socrates… I hope you remember!), but also formulated an autonomous thought made to become the basis of the concept of “ideal” and “metaphysics” which comes from the Greek μετά (/meta/, “through”) and φύσις (/fýsis/, “matter” or “concreteness”), or what we can see or realize through matter. Physis is to be understood as the becoming of the world. However, for the Ancient Greeks, physis does not come from anything, since *ex nihilo nihil fit *(from nothing nothing comes). Therefore, as the “totality of all things,” it includes both the principle from which the world arises and the individual things derived from it.

So Plato and Caltech, what a comparison. But you’ll see, it’s breathtaking. Unlike Socrates, well, I wouldn’t marry this one… Too many ideas and not enough concreteness, still a great intellectual of all respect, but maybe if I had asked him “What do you want to do this afternoon?” he would have answered me with an hour-long monologue on the concept of time, the idea of the afternoon, whether it was real or just an idealized concept that in the end didn’t exist, after all on the other side of the world it wouldn’t have been afternoon, and therefore everything would have become relative. In short, the afternoon would have passed and I, hyperactive, would have gone running for 3 hours after a very long mental loop. I would say no, our relationship wouldn’t have worked.

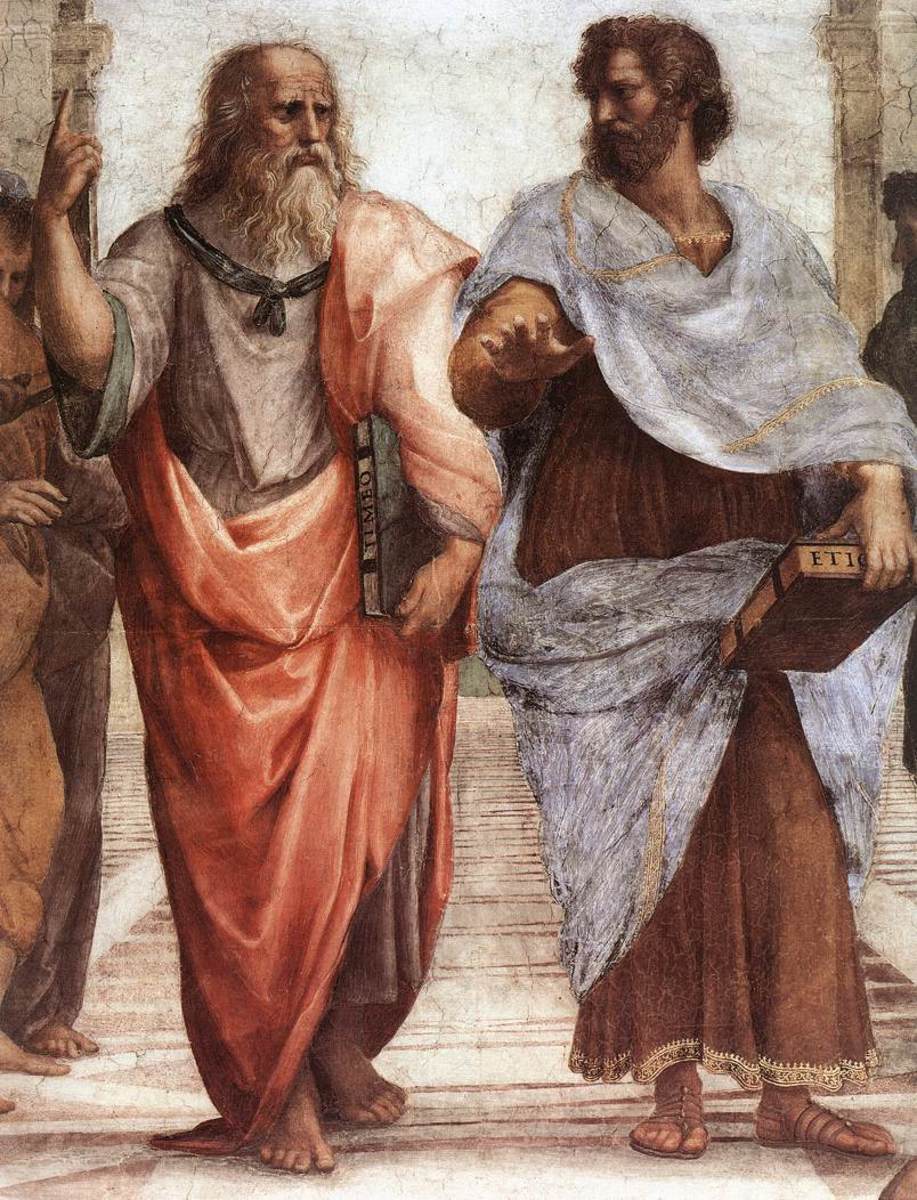

Detail of the fresco “School of Athens”: Plato points his finger upwards to indicate the search for his philosophy, the heavenly origin of metaphysics, and the search for ideas.

Jokes aside, let’s see.

The problem from which Plato’s philosophical reflection starts is: How do you achieve virtue?

His teacher, Socrates, had explained that virtue is the attitude of the wise. The wise is he who knows he doesn’t know and for this reason, shows a desire to know. So let’s go back to the concept of Honor and the search for oneself as virtue, what would be the first words that would come to mind if I said virtue? Loyalty, justice, wisdom… There are many synonyms, but what is it in concrete terms?

Plato takes up this theme and explains that the wise man is the philosopher, or rather, he who is moved by the thirst for knowledge. The philosopher is halfway between the gods, who already know everything and, therefore, are not interested in the search for knowledge, and the ignorant, who think they already know everything and, therefore, do not seek to know.

However, a problem remains open: If the search for knowledge is a virtue, what is the actual object of knowing? Here, Plato’s science, finding concreteness in metaphysics, is tough, perhaps more than any other. Sometimes I reflect, and if you think about it, science, even if it is still to be discovered, is concrete, it is rational and above all material. We can do an experiment and then do it again, we have objects to use, cells, tools, and machinery, but no machine allows us to search for the origin of knowledge. In short, you don’t put the idea of knowledge under the microscope and find its origin… Nor create a rocket to search for it on another planet, or an artificial intelligence program that tells you. So, even if it certainly was and is another type of research, I find it fascinating because it cannot have definitive answers, you cannot write a paper stating all the tests we have done. What does this search for knowledge lead to? For Plato, you can arrive at an ultimate knowledge, which can produce a universally valid moral.

Around this theme, Plato develops his philosophical system that rests on three fundamental themes closely connected:

- The world of ideas

- The connection between soul and knowledge

- Political theory

Let’s focus on his theory of ideas: the central pivot of Plato’s thought. This doctrine revolves around a distinction between:

- The sensible world (= the natural world) in which we know things through a perception that comes from the senses. E.g., a chemical experiment in which we recognize what is happening and we see it.

- The world of ideas (= the intelligible world) in which knowledge does not occur through the senses but through the intellect… Let’s face it, mathematics.

To understand the difference, a very simple example is enough. Let’s think of a series of trees that we can see on the street and that we therefore know with the senses. These trees are different from each other, that is, they are individual objects, one different from the other, however similar they may be, and yet we always identify them with a generic term: “tree”.

This happens because we possess an abstract idea, that is, the concept of a tree.

On the one hand, therefore, we have a sensible world in which many entities appear to us that are perceived. These entities are multiple, changeable (since they can change over time), and imperfect (since each of them is only a particular representation of a universal concept which is the idea).

On the other hand, we have an intelligible world of ideas. These can be defined as immaterial entities (because they are abstract) and eternal (because they never change and their existence is valid regardless of the different circumstances of the natural world). These ideas are placed by Plato in a place that he calls hyperuranion, or: “that which is beyond the sky” from the Greek ὑπερουράνιος, composed of ὑπέρ (/ypér/, above) and οὐράνιος (/ouránios/, “celestial”). Plato therefore wants to tell us that these ideas are beyond the physical world, their validity is universal and is not subject to the change of things. So, everything we are looking for seems useless, and unattainable because it is inherent in the ideal world. When we do research where we compare different states in vitro or external conditions, we cannot think about the mutability of things, this is a Caltech contradiction!

How the statue of Plato was supposed to be in the acropolis of Athens

How the statue of Plato was supposed to be in the acropolis of Athens

These ideas are many, just think of all the universal and abstract ideas that we possess, and according to Plato they can be classified into three large categories:

The ideas of things in the world = such as animals, plants, objects, etc…

Mathematical ideas = geometric figures, mathematical concepts, etc…

Ideas of value = concepts such as love, justice, friendship, etc…

These ideas are the most important in the Platonic classification system, as it means that moral values that are usually considered subjective, according to Plato can instead be defined universally. At the top of the ideas of value is the main idea: It is the idea of good. By good Plato means the perfection of the order of things and, therefore the truth in its most absolute sense. As such, the idea of good is what makes all ideas knowable. In this sense, the idea of good gives unity to the multiplicity of ideas, in the sense that all ideas tend towards good.

Following the steps of his master Plato asks himself how to know the soul once we touch the world of ideas. To understand his reasoning we must start from a presupposition: the knowledge of ideas according to Plato is innate, that is, it belongs to us at birth. But is this true? Especially for the fact that we are here, is knowledge innate for everyone? We commit ourselves, we toil and we study to reach knowledge, through all the problems and studies, but for Plato, it is as if each of us had an innate knowledge that blossoms at birth.

Plato arrives at this theory by arguing that:

- It is not possible to try to know what we already know, because we already possess the knowledge.

- It is not possible to try to know something completely new, because in that case, we would not pose the question of its existence and therefore of its knowability.

This reasoning concludes that when we know we do not start completely from scratch, we already possess a form of knowledge.

The consequence of this conclusion is that knowing is remembering, or revealing something that we already possess but do not remember. Plato calls this process: reminiscence. So it is as if we already know everything, but what we have to do is remember.

Obviously, at this point, a problem arises: how can we know ideas from birth and then be able to remember them in life? The solution for Plato is that the soul and the body are separate: the soul precedes the body and knows the ideas. When it incarnates in a body, according to Plato, it is as if it forgets its knowledge, but can then remember, or activate the process of reminiscence.

Wait, but how many mental confusions, they had other things to think about… Like how to stop waging wars continuously and then force future students to study them all by heart, damn you, including the Battles of Marathon and Thermopylae.

So how is it possible to actually activate memory and therefore elevate oneself from the sensible world, in which we limit ourselves to perceiving what is around us, to the intelligible world of Ideas, or abstract and conceptual knowledge?

Here too, we must distinguish two phases of the development of Platonic thought.

In the first phase, Plato takes up the Pythagorean approach to the purification of the soul. The body tends to anchor us to the sensible world through needs and desires, while the soul must know how to control these instincts and passions to elevate itself and dedicate itself to knowledge. To do this, it is necessary to purify the soul from the material needs of the body.

In the second phase, Plato introduces two interconnected themes: The tripartite division of the soul and the love of Ideas. These themes are presented in the dialogue Phaedrus starting from the myth of the winged chariot.

Sketch of the allegorical winged chariot.

In this myth, the soul is metaphorically represented by a winged chariot. This moves in the hyperuranion and therefore knows the ideas. The chariot is driven by a charioteer who must keep two horses in balance that go in opposite directions: A black horse that pushes the chariot down, and a white horse that pushes it up. When the charioteer is unable to keep the horses in balance, the chariot falls to the ground.

What Plato wants to tell us through this myth is that: the soul is composed of three parts, represented by the charioteer and the two horses. The white horse is the passionate part of our soul, the part that pushes us to fight for values such as justice; the black horse is the concupiscible part, or the part that desires earthly things, therefore driven by the most material needs; the charioteer is the rational part of the soul, which must control instincts, passions, and desires the fall of the chariot to the ground represents the incarnation of a body the more powerful the rational part of the soul is in us, the more our soul has known the world of ideas and therefore the more it is driven to remember.

Shocking how, in the end, everything comes back to knowledge, like our university experience or even a simple reading. Have you ever wondered why we read and our parents read us stories since birth? It is as if we were destined to search for knowledge. We are masks, as wrote Luigi Pirandello, a famous Italian poet: We live experiences that have conditioned us. Yet, deep down there is a skin that is thin and almost afraid of really revealing itself. It is deep down that we feel that white horse pushing us upwards and reaching the ideal knowledge. Furthermore, Plato wants to tell us that love is the desire for what we lack and the attempt to appropriate it. The highest form of love is that of the knowledge of ideas, which is the good that we lack most. Plato concludes that the wise man is therefore the philosopher, or rather the one whose soul is dominated by the rational part and who therefore loves knowledge the most. We are all philosophers, right? We love ratio, as reason is termed in Latin, but also rational spirit.

Adding it all up! The Platonic system is a dualistic, vertical, and metaphysical philosophical system:

- Dualistic because there are two degrees of knowledge. On the one hand, relative truths – which arise from experience -, on the other, absolute truths – which arise from the knowledge of ideas. The knowledge that comes from experience is imperfect in itself, but it is all the more adequate the closer that particular experience brings us to the absolute idea

- Vertical because ideas and sensible things have different degrees of validity. :At the top of this system are the ideas, which represent being. Plato defines the knowledge of ideas as Ἐπιστήμη (episteme) or knowledge that finds its full foundation in itself. It is interesting to define that for him there was a sub-knowledge, that is, opinion. It represented the conditioning of the soul concerning a rational and clear reality

- Metaphysical because it presupposes the existence of something beyond experience in nature. Ideas are metaphysical entities, that is, they exist beyond nature, the physical world.

All these aspects are summarized in the most famous Platonic myth, that of the cave, narrated in the Republic.

The cave, with its darkness, represents the world that we know through the senses, which therefore produces limited knowledge. Leaving the cave leads to the external world, the illuminated world, which represents the true knowledge of ideas. The Sun illuminates the world, which in the metaphor of the myth represents the Good, or the idea that makes it possible to know all ideas.

Leaving the cave is presented by Plato as a tiring journey, as it means leaving the path of knowledge that comes from the senses and getting used to reasoning on a higher level. The one who completes this journey is the philosopher, the sage, the one who frees himself from the chains that keep him nailed inside the cave. The problem, for the philosopher, is that his task is to return to the cave and educate others to the knowledge of ideas—thus carrying out his political function—but the return is dangerous, as those who are not driven to seek knowledge would refuse to follow the same path of ascent towards ideas.

We find a relationship with teaching, the desire to achieve clarity. Metaphorically, for me in the bio-chem sector, it is seeing a clean slide, a palpable result. For others, it can be a mathematical or physical formula, a drone, or a program. We, therefore, reach the Sun, which then in California, is quite simple to find to search for ourselves and navigate the dark meanders of the mind and not only in those of Baxter. As Dante Alighieri wrote when he leaves Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise in his most important work, The Divine Comedy: “Thence we came forth to rebehold the stars.” This is what Plato asks of us, just as this is what Caltech asks of us: to reach out with our hands and in a tangible way those stars of wisdom, to share them and bring them to the world to make it better.