Epicurus at Caltech: The Garden of Serenity and Science

Epicurus at Caltech: The Garden of Serenity and Science

In Search of Meaning Beyond the Microscope

There is a question pulsing quietly beneath the surface of every lab bench, every line of code, every equation scribbled onto a whiteboard: Why are we doing this? Is it for discovery, for prestige, for the betterment of humanity—or something more elusive? At Caltech, we pride ourselves on pushing the boundaries of what is knowable, and we do, no one says the opposite. We decode the stars, manipulate the quantum, edit genes and simulate the brain. But in a world full of complexity, speed, and ambition, can knowledge make us wise? Can science teach us how to live well?

In the fourth century BCE, a Greek philosopher named Epicurus offered a radical answer. He did not build a temple to logic or a shrine to mathematics. He built a garden—a quiet, inclusive space where the pursuit of truth was not an end, but a path to serenity, freedom, and joy, like the one near Dabney Hall. In that garden, knowledge was not divorced from life but intricately woven into it. And philosophy was not an ivory-tower exercise, but a medicine for the soul.

Today, as we confront the challenges of a hyperconnected, hypercompetitive academic world, perhaps the Garden of Epicurus has something to teach us still. Perhaps, in a way, Caltech is its modern incarnation—a place where brilliance and solitude, ambition and stillness, knowledge and meaning, coexist.

The Philosopher’s Garden, Athens, 1834 by Antal Strohmayer (1834).

The Garden: A New Philosophy of Living and Learning

When Epicurus opened his school in 306 BCE, he did something unheard of: he closed his back on the elitist schools of the Academy and the Lyceum and opened an inclusive space to all—women, slaves, foreigners, and the disenfranchised. The Garden was not a setting for argument or political power; it was a refuge of thought and friendship, a sanctuary for individuals who sought not glory, but peace of mind. His students did not just study—they lived together, sharing meals, ideas, and emotions in a kind of philosophical community. They read, wrote, and thought. They celebrated friendship. They sought wisdom not for its own sake, but because wisdom made for happiness.

At Caltech, where collaboration routinely trumps competition, where small classes forge intense intellectual intimacy, and where the pursuit of fundamental truths can be intensely personal, we can sense whispers of that ancient Garden. The lab is a kind of sanctuary, the relationship between advisor and advisee a philosophical dialogue, the late-night coding session a meditation on the meaning of life. Of course, unlike the tranquil Garden of Epicurus, at Caltech the pursuit of happiness regularly involves sleep deprivation, subsisting on vending machine fare, and convincing yourself that debugging at 3 a.m. is just another form of “philosophical contemplation.”

Philosophy as Therapy: The Fourfold Cure

For Epicurus, philosophy was not about abstract speculation—it was about healing. He believed humans suffer because they cling to false beliefs: fear of gods, fear of death, anxiety about pain, and the illusion that happiness is unreachable. To counter these, he proposed the tetrapharmakos (tetra= four) or fourfold remedy:

-

Don’t fear the gods—they don’t interfere with human affairs.

-

Don’t fear death—it is simply the end of sensation.

-

Pain is manageable—either it is brief, or it is mild.

-

Happiness is attainable—if we live wisely and simply.

It’s a kind of philosophical inoculation, a vaccine against existential despair. It invites us, even today, to reframe our fears. Although let’s be honest, if Epicurus had ever tried debugging a finicky codebase at 4 a.m., he might have added a fifth remedy: “Don’t fear the compiler—it just doesn’t like you.“It invites us, even today, to reframe our fears. How many students, researchers, postdocs, faculty—even Nobel laureates—are secretly burdened by the anxieties named by this philosopher? Epicurus’ reminder is timely: true excellence requires inner peace. The mind cannot flourish in turmoil. The best science may come not from ambition, but from clarity, calm, and freedom from fear.

Clinamen and the Physics of Freedom

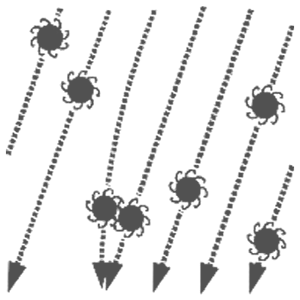

A representation of clinamen, by Petra Tomljanovic.

Epicurus borrowed atomism, the idea that the universe is made up of indivisible particles moving in a void. But he supplemented it with something brilliant: the clinamen, a nondeterministic deflection from the course of the atoms. The tiny, unguided swerve offers the opening to free will in an otherwise determined universe. This concept is not metaphorical. It hits very close to modern physics—specifically, quantum indeterminacy. Like Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, the clinamen breaks the chain of necessity. The world is not a machine—it is a field of possibilities. Of course, if Epicurus had to deal with particle accelerators perpetually in need of repair, he might have just called the clinamen “equipment failure.” Here at Caltech, we are taught uncertainty not just in quantum mechanics, but in neuroscience, in computation, and in climate science. We build models, but we know their limits. Epicurus instructs us that freedom—human freedom—lies in those limits. That the uncertainty of nature is not a flaw, but a feature that makes agency, creativity, and moral responsibility possible.

Pleasure Redefined: The Science of Joy

Epicurus has often been mischaracterized as a hedonist. But his concept of pleasure was not sensual. His ideal pleasure was serenity, not thrills, relief from pain, not overindulgence. He distinguished between:

-

Natural and necessary pleasures — the necessities like food, water, shelter, and friendship.

-

Natural but unnecessary pleasures — luxuries like fine food or expensive clothes.

-

Vacant and hollow pleasures — wealth, power, fame.

The first one alone leads to permanent joy. The rest, he warned, leads to dependency, anxiety, and pain. The judicious person chooses pleasures that bring harmony, not disturb it. This is particularly relevant to Caltech life. With a high-performance environment, it is simple to fall into over-working, over-achieving, and over-consumption. How many of us have worked all night to try to capture the “vain and empty pleasure” of a perfect dataset, or sacrificed a natural and necessary pleasure (such as sleep) on the altar of productivity? Epicurus offers a different model: a life of simplicity, reflection, and sustainable joy. One where happiness is not measured in accolades, but in moments of quiet fulfillment. Maybe, just maybe, the next time you’re tempted to skip lunch to squeeze in another hour in the lab, you’ll pause and think: What would Epicurus do? (Spoiler: He’d eat the sandwich. And probably take a nap afterward.)

Friendship Over Fame: A Different Kind of Community

Epicurus believed friendship to be the highest good. Unlike romantic love or fame, friendship brings pleasure without fear, closeness without loss of autonomy. At his Garden, relations were egalitarian, not hierarchical or transactional. At Caltech, where teamwork is everything, where friendships are forged in the crucible of shared discovery, this ideal has resonance. The bonds we form in research groups, dorms, and seminars persist longer than our experiments. These are the true legacy of our stay here. Face it, nobody’s going to be recalling that single problem set you aced, but they’ll recall the time you and your classmates liberated the fire alarm with some “creative” lab experiment.

Epicurus would argue that friendship in and of itself is a practice of philosophy—a living of our ideals. In a world that prizes achievement, he reminds us that being good to one another is itself a kind of excellence. So maybe the next time a friend shows up at your door at 2 a.m. with a crisis over their thesis, you’ll think of Epicurus, open the door, and offer them a snack. Because, let’s face it, snacks are the cornerstone of all great friendships.

Against Fear, Toward Wonder

Epicurus rejected superstition. He believed that knowledge of the natural world frees us from irrational fears. Thunderstorms, earthquakes, eclipses—these were not omens or punishments from the gods, but material happenings. Knowledge, he believed, frees us. This is perhaps where the comparison with Caltech is most fitting. Here, we want to know so that we can rid ourselves of ignorance, not so that we can cling to control. We don’t fear the unknown—we go out there to explore it. Though let’s get real, if Epicurus had ever sat through a 3-hour quantum mechanics lecture, he might have been somewhat intimidated by the unknown too. Epicurus encourages us to do more than merely explain phenomena. He asks us to take back our emotional lives from fear, to leave space for wonder without terror, for awe without anxiety. So, the next time your experiment goes wrong—or your code spews out an error message in what appears to be ancient Greek—call upon your inner Epicurus. Don’t panic. Instead, let curiosity drive. Who knows? Maybe the “error” is the beginning of a breakthrough (or, at the very least, a good joke to chuckle over later).

The Garden Is Still Alive

Epicurus was maligned for centuries. Christians called him heretic. Dante placed him in Hell. The Stoics dismissed him. But quietly, persistently, his ideas survived—in fragments, in letters, in the quiet corners of philosophy. And perhaps, without knowing it, we are living out his vision here at Caltech.

Not because we quote him or build gardens in his name. But because we pursue knowledge in a spirit of humility. Because we value collaboration over conquest, depth over display, meaning over noise.

“We are mortal by nature, but infinite through reason.” – Epicurus

In a world chasing speed, scale, and spectacle, Epicurus offers a slower, saner horizon. One where science and serenity walk hand in hand. One where we are not just brilliant minds—but flourishing human beings. And perhaps, just perhaps, this is the most revolutionary idea of all.