What Cuts Kill: On Wonder and Revolution

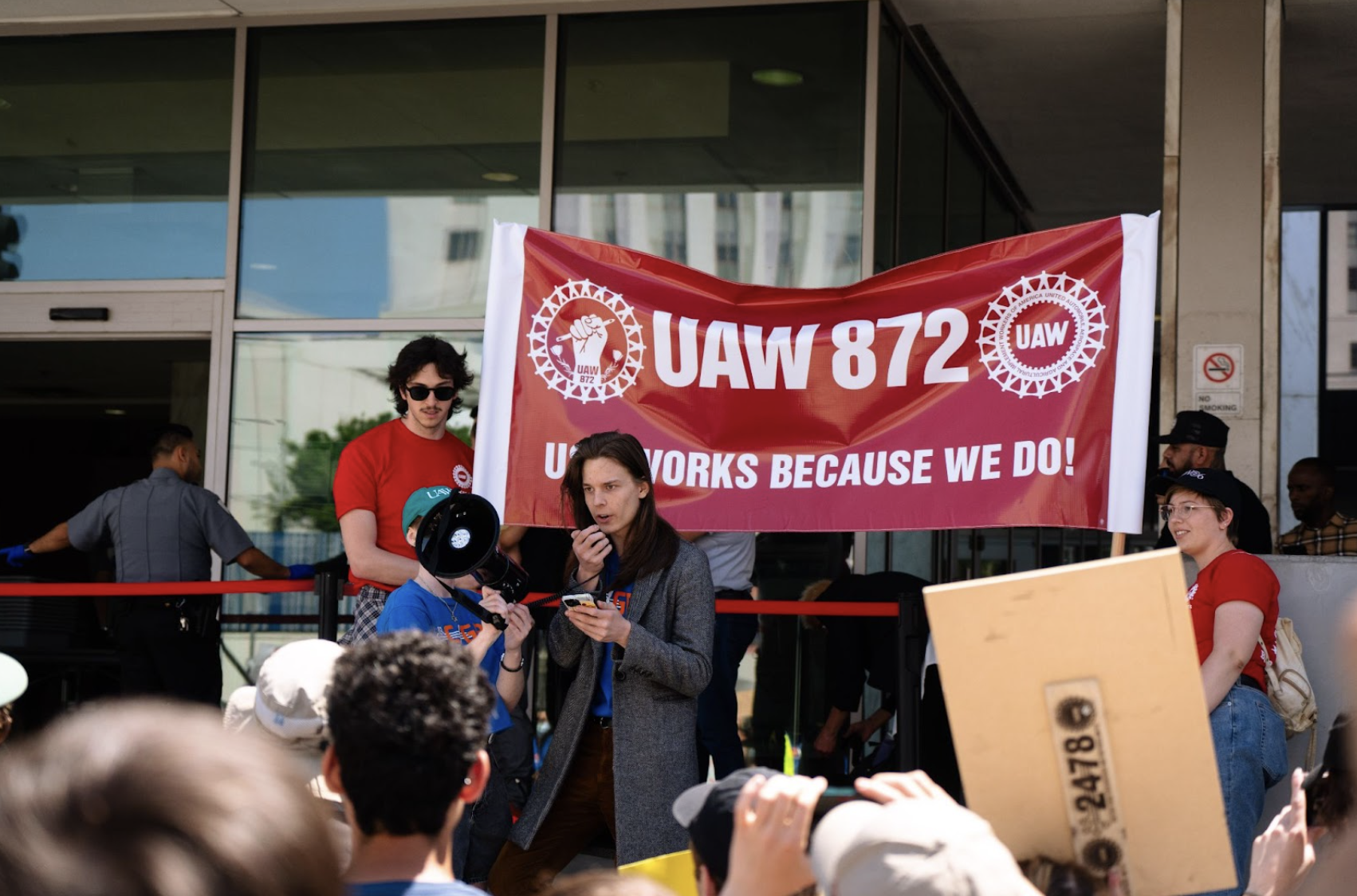

My delivery of the speech on the steps of the Federal Building. (Photo: Alex Ramirez)

At the Kill the Cuts rally on April 8th, I gave the following speech to Caltech and USC contingents in front of the 300 North Los Angeles Federal Building. I hope its words resonate with the current scientific/political/cultural moment. They represent my truest feelings, the joyous and the vitriolic, as best as I can compress and verbalize them.

Hello, everyone. I speak to you today from the perspective of someone on the highly basic end of the scientific spectrum, working in theoretical high energy physics, who has been determined since I knew of its existence to go to grad school and earn a Ph.D.

As it happens, scientific funding in this country has never been an easygoing enterprise. Federal funding for science as a percentage of the GDP has been on a steady decline since the 1960s, and with these unprecedented threats to the NIH and NSF, we are watching that decline massively accelerate—just as the problems we face as a society grow ever more complex, more urgent, and more global.

At best, the justification for these cuts is a flimsy pretext based on the supposed shortcomings of DEI. At worst, it is a flagrant abandonment of the scientific enterprise in favor of an authoritarian with no tolerance for an informed republic.

And the skies are already darkened. As an undergrad, friends of mine have had funding from grad schools suddenly rescinded; scores of undergrad research programs have been forced to downsize; and the general climate of joining the scientific workforce, let alone advancing in academia, has never looked bleaker. This nation cannot, in good conscience, transmit this message to the next generation of scientists: that their passion is a liability, their curiosity dispensable.

Let me ask you:

Can we do this to the next generation?

Can we do this to the next generation?

Allow me to emphasize something elementary. The goal of science, particularly that of basic research, is to—according to the best of our ability as a species—eke out a genuine form of truth. That is, armed with the immortal instruments of curiosity, skepticism, and humility, we can erode our biases and reshape our prejudices, moving ever closer to a clearer, more sincere appreciation of the world as it truly is. This is, firstly, not to extinguish the experience of wonder, but to serve its ultimate expression, and in so doing, best cherish what beauty accompanies the shape of the cosmos or the weirdness of the quantum.

This fact was especially and famously well-captured by the 1969 congressional testimony of Robert R. Wilson, the founder of Fermilab and a champion of high energy physics in America. At the suggestion that findings from a particle collider confer no national value, he gave this unflinching reply: “[The collider’s] new knowledge has all to do with honor and country but nothing to do directly with defending our country except to make it worth defending.”

Also demanding emphasis is what, for the impatient industrialist, science can secondarily accomplish: the enrichment of society with what applications emerge, often incidentally, from pure intellectual curiosity.

So goes the story of quantum mechanics, initially charged as it was by an honest desire—really, an obsession—to resolve these numerous bizarre paradoxes of atomic spectra and radiation.

The resulting formalism, immortalized by Werner Heisenberg’s paper published nearly a century ago in July 1925, is arguably the bedrock of modernity. Understanding the quantum behavior of electrons in solids led to the invention of the transistor in 1947 at Bell Labs, this gave us computers, smartphones, and the entire digital age; the quantum theory of light and stimulated emission led to the development of lasers in the 1960s, used now in fiber optics, laser medicine, barcode scanners, manufacturing, and precision measurements; the physics of nuclear magnetic resonance, based in quantum spin, led in the 1970s to the MRI machine, without which the modern hospital would not exist.

How in the world could Heisenberg have foreseen that questions about atomic spectra would lead to smartphones and MRI machines?

Of course, my point is that scientific research, ultimately of all kinds, is immeasurably valuable—both intrinsically, in fact having all to do with honor and country, as another Wilson once said; and in its manifold applications, which the nature of basic science in particular renders unforeseeable. To impose not just funding cuts, but indiscriminate, sweeping reductions across the board, is to strike at the very heart of the inexhaustibly rich legacy of discovery and innovation that once propelled America to the forefront of global leadership in the first place.

We protest not just on behalf of scientists. We stand up here today for a vision of civilization that sees curiosity as a virtue, that prizes knowledge as a public good, and that believes in a future worth building as a result. For isn’t that the kind of future we owe ourselves—one founded not on fear or ignorance, but on wonder, discovery, and truth?

So to Congress, to the administration, and to anyone willing to listen:

Fund wonder. Fund discovery. Fund what truly makes America great.

Thank you.