Scientific Discovery as Sacred Encounter: Reflections on Quantum Fields and Faith

The second floor of Kerckhoff had an unusual stillness that evening. People trickled into the small library room for the Science and Faith Examined (SAFE) talk, uncertain yet curious. I sat near the back, notebook open, listening to Tara—a physics PhD student and president of GCF—unfold her reflections on quantum field theory and the Bible. The hum of conversation faded as she spoke about particles, fields, and the hidden architecture of creation. Her words carried not only the weight of scientific precision but also the wonder of a believer searching for coherence between equations and eternity.

As she described the universe as a network of fluctuating fields, I felt an ache of recognition. I, too, had wrestled with the distance between what I study in the lab—the coded dance of molecules, the stubborn complexity of cancer cells—and what I feel when I stand under a cathedral ceiling or read the Psalms. The quantum and the sacred seemed, at first glance, to inhabit different languages. Yet something about Tara’s talk suggested that both reach for the same horizon: the invisible made knowable, mystery glimpsed through pattern.

I have often felt small on this sprawling campus, dwarfed by the intellect around me, chasing data that never fully align. And yet, in those moments of humility, I glimpse the possibility that my research—the effort to heal broken cells—participates in a grander tapestry of restoration. Perhaps, as both physicists and theologians like John Polkinghorne and Ian Barbour suggest, knowledge itself is an act of faith, an echo of divine curiosity. Quantum field theory, with its unseen fluctuations, may not only describe the universe but also whisper something about how God sustains it: in motion, in uncertainty, in relation.

The Quantum Tapestry: Where Physics Meets the Divine

Quantum field theory suggests that what we perceive as solid matter is ultimately the manifestation of invisible fields—continuous and dynamic sheets of energy whose vibrations give rise to particles. The universe, in this view, is not made of discrete building blocks but of intertwined forces continually fluctuating, appearing, and vanishing in the silence of subatomic space. Tara’s explanation of this theory that evening at SAFE felt curiously intimate; it evoked an ancient truth that theologians had voiced long before quantum physics gave it mathematical form: that creation is sustained moment by moment by an underlying presence, unseen yet active.

![https://katychristianmagazine.com/2022/04/15/yes-science-and-religion-can-co-exist/][image1]

From “Yes, Science and Religion Can Co-Exist.” (Photo: Katy Christian Magazine.)

John Polkinghorne in his Belief in God in an Age of Science (1998), himself both physicist and priest, often wrote that quantum uncertainty reveals “a creation allowed to make itself.” To him, the indeterminacy woven into matter testified not to chaos, but to divine generosity—the Creator granting autonomy to creation. Ian Barbour (1997) echoed this harmony, suggesting that science and faith describe the same reality through distinct, yet complementary, methods of interpretation. For both, faith does not oppose empirical reasoning; it frames it within purpose. Similarly, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin envisioned the cosmos as charged with divine life, evolving toward an ultimate union he called the Omega Point. In his mystical language, the physical and the sacred are entwined expressions of one creative pulse.

When the speaker reflected on these ideas, she pointed out that quantum theory’s relational structure—that particles gain meaning only through interaction—offers a fitting mirror of theological thought. The God of the Bible, she noted, is relational: a trinity of love and mutual indwelling, an eternal communion. Likewise, the physical world emerges from relationships rather than isolated entities. Nothing exists alone; everything participates in the whole.

Listening to her, I began to sense that quantum physics and theology might share an underlying metaphor: that of interconnected being. If creation is indeed a continuous flow of divine energy, then perhaps the fields described by physics echo what Scripture names as Spirit—a breath permeating all existence (Genesis 1:2). Theologian Philip Clayton in his Mind and Emergence (2004) suggested that divine action might be subtle, manifesting not as intervention but as influence within the openness of physical processes. This notion fits within quantum indeterminacy, where potential and realization coexist until observation. It invites an understanding of God not as a distant artisan but as an abiding presence woven into every vibration of reality.

From Quantum Physics, Relationality and the Triune God. (Photo: Teilhard de Chardin)

From Quantum Physics, Relationality and the Triune God. (Photo: Teilhard de Chardin)

As Tara closed her slide deck with an image of overlapping waves, I thought about how belief often stands at that same threshold between the measurable and the mysterious. Quantum field theory does not explain God, yet it gestures toward an order and beauty that faith calls divine. In this intersection, both the scientist and the believer become co-seekers, looking into depths where knowledge gives way to wonder.

The Microcosm Within: Protons, Particles, and Divine Patterns

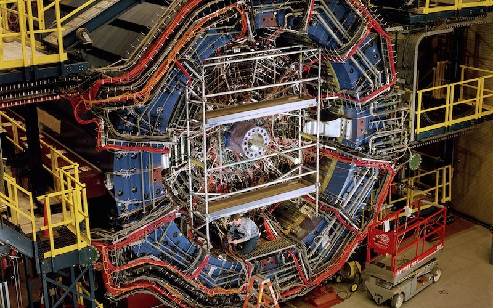

The research conducted at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) offers a fascinating parallel to these theological reflections. Scientists at RHIC have been peering into the teeming microcosm within protons, examining how quarks and gluons interact through properties such as spin and color charge. This color charge—not visible color, but a fundamental property that comes in three forms combining to create neutrality—mirrors the trinitarian concept Tara discussed. Just as red, green, and blue light combine to form white light, the three color charges of quarks must unite to achieve balance.

The STAR detector (for Solenoidal Tracker at RHIC), among the four experiments at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) in Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL), New York. (Photo: BNL)

The STAR detector (for Solenoidal Tracker at RHIC), among the four experiments at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) in Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL), New York. (Photo: BNL)

The experiments at RHIC’s STAR detector reveal something profound about the nature of reality: that beneath the apparent simplicity of protons lies extraordinary complexity. By colliding polarized protons and analyzing the resulting particle debris, scientists have measured effects of the color interaction—the basis for the strong nuclear force binding quarks within protons. This measurement tests theoretical concepts essential for mapping the proton’s three-dimensional internal structure.

What strikes me about this research is its resonance with theological inquiry. Both seek to understand what cannot be directly observed. The scientists cannot see quarks or gluons directly; they must reconstruct their behavior from the traces they leave behind. Similarly, theologians seek to understand the divine through its manifestations in creation, through Scripture, through human experience. The W bosons produced in RHIC collisions decay almost instantaneously into electrons and neutrinos—particles that are difficult or impossible to detect directly. Yet by tracking the jet of particles that recoil in the opposite direction, scientists can reconstruct what happened in that fleeting moment of creation.

This methodology mirrors contemplative practice. We cannot grasp the divine directly, but we can observe its effects—the transformations it works in matter and spirit, the patterns it leaves in the fabric of existence. The ‘single transverse spin asymmetry" that RHIC physicists measure—an imbalance in particle production depending on proton spin orientation—reveals something fundamental about how nature operates at its deepest levels. It shows that even in the subatomic realm, there is order, pattern, and relationship.

Smallness as Vocation: Finding Meaning in the Microscopic

As the room slowly emptied, I lingered in my seat, thinking about the idea that every field vibration, every quantum fluctuation, carries meaning only through connection. That sense of interrelation mirrored something deeply personal to me. On a large campus, surrounded by voices louder and minds quicker, I often feel like one tiny particle in a vast field. My research—long hours spent manipulating cells to find ways to halt cancer’s advance—can feel both monumental and minuscule. Yet when I consider what Tara and the theologians she referenced had suggested, I realize that my smallness is not insignificant. Rather, it reflects a divine pattern: meaning unfolding through the minute, miracles arising from the microscopic.

Biology magnifies this truth daily. The human body thrives because of the choreography of unseen processes: DNA unwinding, proteins folding, neurons firing in silent sequence. Each living system echoes the principle of the quantum—hidden layers of motion giving rise to the tangible. The 20th-century Jesuit thinker Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1955) saw this as no coincidence. He imagined evolution as the universe awakening to consciousness, a gradual unfolding of divinity within matter. In his view, every molecule participates in the spiritual ascent toward wholeness; every cell carries divine potential. My cancer studies, then, are not merely biochemical puzzles—they are small acts in the universal drama of healing, each experiment a humble collaboration with creation’s continual self-restoration.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955), French philosopher and Jesuit priest. (Image: Prisma/UIG/Getty Images)

That thought challenges the loneliness I sometimes feel as a student scientist. It reframes my work within something vast yet personal: a participation in divine creativity. In theology, humans occupy a middle ground—creatures capable of questioning the cosmos that birthed them. Similarly, in quantum physics, observers influence reality through their recognition; in biology, life sustains itself through feedback and response. These patterns suggest that consciousness and existence are not detached elements but mutual reflections.

John Polkinghorne in his later Quantum Physics and Theology (2006) wrote that science gives us the “how,” but faith points toward the “why.” Sitting there, I began to see the lab bench as an altar of inquiry. The movements of pipettes, the fluorescence of stained cells, the fluctuations in quantum fields—all gestures of the same cosmic curiosity embedded in the divine image. God, as some theologians propose, might be felt most profoundly where the infinitely small meets the infinitely meaningful. Quantum fields vibrate unseen; so do prayers whispered in the silence between hypotheses.

Uncertainty as Sacred Space: The Convergence of Knowledge and Trust

One of the most profound tensions in both science and faith is the desire to know and the willingness to trust. During Tara’s lecture, as she described how quantum fields defy deterministic predictability, she smiled slightly and said, “Faith lives where certainty leaves off.” That line unsettled and comforted me at once. It echoed experiences in the lab where results never align perfectly, where experiments veer unexpectedly, and where I am called to continue believing in the process even without clarity. Science and faith both demand perseverance amid uncertainty—each a different expression of commitment to truth.

Ian Barbour in his Religion and Science (1997) proposed that science and religion inhabit “distinct but complementary domains of inquiry,” while science analyzes through verification and faith approaches reality through trust and meaning. The more I contemplate this, the more I sense that both are languages for understanding one creation. As a biology researcher, I search for molecular explanations of life; yet as a person of faith, I respond to life’s call with awe. John Polkinghorne (2006) suggested that “faith is motivated belief”—not blind acceptance, but trust shaped by experience and reason. That resonates each time a hypothesis fails but my curiosity persists. Every repeated experiment becomes an act of hope, a small prayer disguised as scientific method.

Tara’s reflections illuminated how these modes of knowing and believing interact rather than collide. She spoke of her struggle as a physicist who sought beauty both in mathematical symmetry and Scripture. To her, the wave functions of quantum mechanics resemble verses of a liturgy—patterns revealing invisible coherence. Listening, I recognized echoes of my own internal dialogue: the scientist skeptical of unsupported claims and the believer unafraid of questions. These two voices no longer seem opposed; they form a duet, each keeping the other from absolutism.

Teilhard de Chardin’s The Phenomenon of Man (2006) might have called this the “convergence of truth,” where the pathways of intellect and spirit ultimately meet at a horizon of meaning. Similarly, theologian Sarah Coakley in her God, Sexuality, and the Self (2015) describes contemplation as a method of knowing distinct from analysis but equally disciplined—a surrender that invites insight beyond control. In that sense, both equations and prayer can be acts of attention. The scientist studies patterns in matter; the believer contemplates order in mystery. Each posture opens a window into reality’s depth.

As I walked back from Kerckhoff that evening, the boundaries felt thinner—the gaps between laboratory and chapel, literal and figurative light. The fluorescent glow of my research lab no longer seemed separate from the candlelight of faith but part of a continuous illumination. To believe is not to abandon reason, and to reason is not to exclude wonder. The dialogue between the two refines both, teaching me to look closer, question deeper, and love the search itself.

In the end, the intersection of quantum field theory and faith was not, I realized, an attempt to force agreement between science and spirituality. Rather, it was an invitation to inhabit both—to dwell in the mystery that neither can fully contain. I began to see that uncertainty is not the enemy of faith but its atmosphere, just as indeterminacy is not the flaw of creation but its freedom.

Feeling small on campus, I used to equate significance with scale. Yet through this dialogue between science and faith, I have come to understand that wholeness begins in the smallest interactions—whether in the subatomic dance of particles or in the microscopic layers of living tissue that I study. Each whisper of movement, each random fluctuation, participates in the divine rhythm of becoming. Faith gives that rhythm shape; science gives it texture. Together, they form a harmony that humbles and inspires.

When I returned to my lab bench, the pipettes and microscopes still surrounded me, but their silence spoke differently then. The patterns I chased were no longer detached from meaning but were filled with resonance—the same resonance that vibrates through quantum fields and the same stillness that Scripture calls the breath of God. To know, to believe, to wonder—these are not opposite pursuits but one continuous act of reverence before the mystery of existence.

The work at RHIC continues, seeking to nail down the “sign change" in particle asymmetry, hoping to confirm theories about color charge interactions. Scientists there plan future electron-ion collider experiments to produce three-dimensional pictures of the proton’s momentum structure. These are not merely technical achievements; they represent humanity’s persistent desire to see more deeply into the fabric of reality. And in that persistence, I recognize something sacred—the same impulse that drives contemplatives into silence and researchers into laboratories, the hunger to encounter truth in all its forms.

Perhaps this is the gift of that evening at Kerckhoff: not answers, but a deeper comfort with questions. Not certainty, but trust in the process of seeking. Not a merger of science and faith, but a recognition that both arise from wonder and return us to it, transformed.

References

Barbour, I. G. (1997). Religion and science: Historical and contemporary issues. HarperCollins.

Clayton, P. (2004). Mind and emergence: From quantum to consciousness. Oxford University Press.

Coakley, S. (2015). God, sexuality, and the self: An essay “on the Trinity”. Cambridge University Press.

Polkinghorne, J. (1998). Belief in God in an age of science. Yale University Press.

Polkinghorne, J. (2006). Quantum physics and theology: An unexpected kinship. Yale University Press.

Teilhard de Chardin, P. (1955). The phenomenon of man. Harper & Brothers.