Should You Play Chants of Sennaar?

When suggesting games to friends, I’ll often get a response along the lines of “Oh, I’m not good at games.” This statement can be a bit confusing in that it is so general. What does it mean to be “good at games?” There are definitely types of games one might not be good at, for example I suck at shooters, but I find it hard to believe that one can be bad at all games. I think it comes from a common misconception of video games among non-gamers that all video games are based around combat or some amount of physical skill surrounding reaction time and hand-eye coordination. Chants of Sennaar is a counterexample to this idea.

Chants of Sennaar is a puzzle game through and through. There is no combat. The only slight control skill needed is in a few stealth sections that are basically just interactive puzzles. It’s a game that I would recommend, but with a few warnings.

The story centers around the tower that the player finds themselves waking up in. Each level of the tower contains a different society with a different language, culture, and people. The main character has no name or knowledge of where they are. You’ll simply wake up and learn a new language. Many things are left unexplained and left to the player to understand. This has its pros and cons. For the most part, it creates a very satisfying experience where one can feel quite clever. On the other hand, it can be frustrating if you get stuck and are led to brute force a puzzle as a result. A game has never made me feel more smart, but also so dumb.

Something admirable surrounding the gameplay is that English, or whatever language you select in the settings, is used only to explain how to play the game. It is never used as part of a puzzle or to tell the story. This means that by design the player should not need any outside knowledge besides a basic feel for language. However, it also means that it can be hard for a player to perfectly understand and solve the puzzles without brute forcing. This lack of straightforward explanation is the source of any confusion that comes from a puzzle. I’ll admit that there were times where I had to look up a walkthrough because I was too frustrated, but in reading the walkthrough I could clearly see how the pieces set before me would’ve lined up if I had the correct idea (except for one incident).

It is undeniable that the puzzles are cleverly designed, but the necessity of that singular spark can be an issue. As the game progressed and the puzzles got harder, I got the feeling that developers also developed a bit of blindness to how a player would approach and solve their puzzles. This feeling only grew towards the end of the game and the complex but simple puzzles that give you the last language.

If you want my spoiler-free recommendation and experience, here it is. I spent around $20 for the physical Switch cartridge, and it took me around 10 hours to get the true ending. This fails the commonly passed around measure of value: $1 per hour of gameplay, but I would say it’s worth it if you can find it on sale (which if you buy it on Steam is extremely likely). Chants of Sennaar is a beautiful game with a unique concept. I can’t think of another game that is remotely similar.

However, if you want my spoiler-full experience, keep reading.

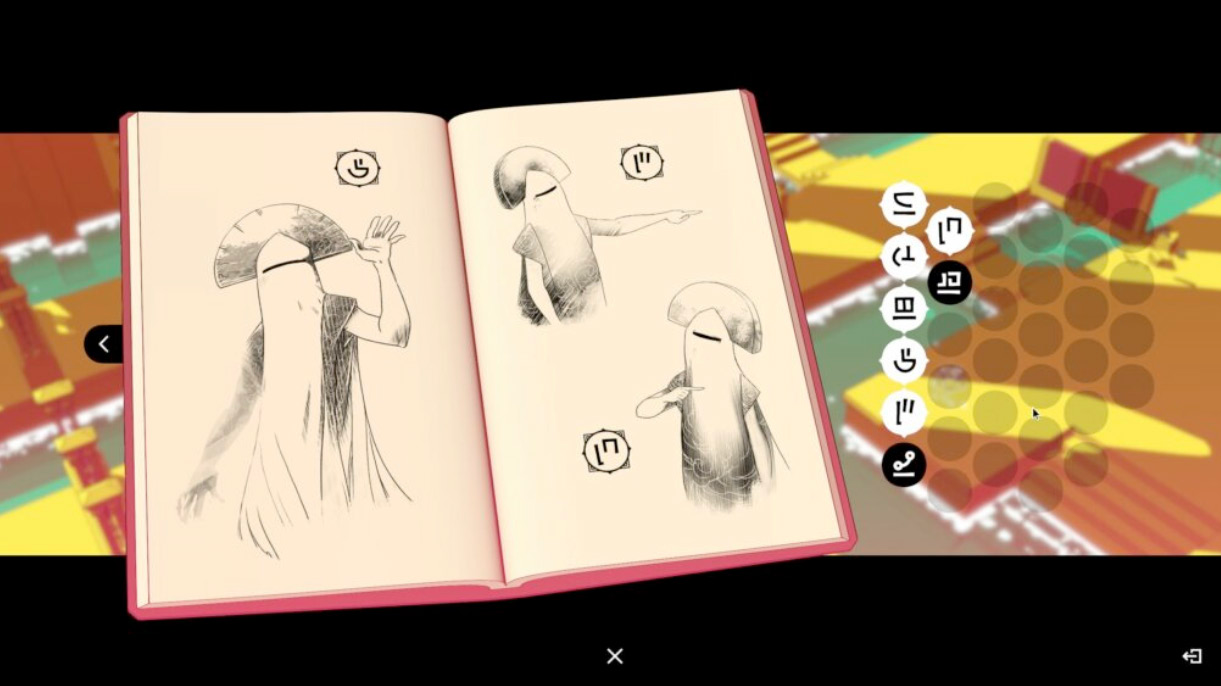

The game starts with the devotees, sadly my favorite level. You are initially presented with a locked door and a lever. The door has a symbol next to it, the lever has a symbol at the top and one at the bottom. When activated, the door opens. The meaning behind the lever symbols immediately becomes clear. Then we meet our first inhabitant of this world, waving their arm signaling you to follow them as you make your way through a series of simple lever puzzles. As they point to themselves and to you, it is easy to connect which symbols represent what. Once you’re done with this short series of puzzles, you’re given the first page of the journal. The pictures are clear in what they depict: a greeting, pointing at “you”, and pointing at “me.” A simple but effective puzzle.

The comparison among languages is precisely where the details of Chants of Sennaar shine. In particular, you can see that the language used will reflect each culture’s values and build in complexity on top of the previous.

The devotees have the most basic language. Plural is conveyed by the repetition of symbols (“man man” to mean “men” for example) and the symbols are meant to be more logographic. Nouns for people will share an L shaped symbol (as seen in “you” and “me”). Symbols for buildings share a box-like structure. It is the easiest to decipher and that’s by design.

The warriors introduce the concept of negatives and an “-s” like symbol to indicate plurality. We also see a difference in how the devotees and warriors view the world. While devotees clearly see themselves as pilgrims, warriors are influenced by the “chosen” bards above and view devotees as “impure.” This explains why they have refused to open the door for them. Additionally, they place a large emphasis on labor, honor, and duty. We can see this in how the fortress they occupy has groups marching in formation through the halls and those that aren’t marching are moving things. Even the shape language of their symbols seems to communicate their rigid and militaristic view as it is filled with straight lines and sharp angles.

The bards have a different sentence structure compared to all the other languages. Instead of subject-verb-object, the bards will conjugate to object-subject-verb. Additionally, their symbols are connected to each other when written somewhat similar to how letters in Arabic are connected. Among the first new symbols you’ll encounter are “beauty”, “music”, and “comedy.” They have a more rounded language that seems to fit their carefree attitude. You’ll also notice that they really like the word “idiot”, often using it to describe the other groups in the tower. The bards are also where I first looked up a walkthrough for a puzzle. This came courtesy of a very complicated series of tunnels that you must navigate with no map provided. Without a walkthrough, I probably would’ve wandered in circles, not found the compass I needed, gave up, and never touched the game again. A really beautiful level though.

The alchemists pull back on grammar complexity, being more simple than the bards, but introduces complexity in learning about their number system. This also led me to my least favorite puzzle of the game. Each number is based around a singular line in the middle and surrounding that line is essentially four quadrants. Each digit then has a particular shape associated with it as given by the number glyphs that you translate. If that digit is in the top left quadrant, it represents thousands. If it’s in the top right quadrant, hundreds. Bottom left, tens. Bottom right, ones. However, this idea is simply not conveyed very well. From what I understand, you’re supposed to get this from the strange almost calculator-like machine in a lab. But this machine has two lines of input which can really confuse things. Even in walkthroughs, how you’re supposed to figure this system out on your own is not explained. So while I admire this unique number system and can see how it reflects the alchemists’ pursuit of science, it frustrates me and represents the pitfalls of the level design. Still, the alchemists have what I consider the best designed language. The glyphs are much more complicated and harder to write than the previous languages, but they also share elements that create groups among them. For example, verbs share a similar arc. Elements, yes like those in the periodic table, share a triangle. The glyph for brother kinda looks like a person putting their arm around another person. Things like that make it the most detailed language.

Finally, the anchorites. This language was the easiest, fastest, and most frustrating to complete. This is because all of the glyphs you need to know are given to you through a translation puzzle. However, the mechanics to this puzzle (matching up rings of glyphs of different languages) are, obviously, never explained. So you’re supposed to look at it and just know to match up glyphs of the same meaning (keep in mind that you still don’t know the meaning of some of them). Maybe I’m just dumb, but since I couldn’t figure that out immediately I looked at a walkthrough and saved myself some time. Once you know how the puzzle works, the anchorites’ language is basically just given to you. It feels a little like a cop-out. Like they wanted to add another language to advertise a larger number of glyphs, but they didn’t have the time or energy to actually make another set of environmental puzzles surrounding it. The only cool thing they add is that they’re glyphs can be stacked on top of each other to create new meanings.

While the differences are fascinating, I find the similarities more meaningful. Every language has a glyph for the following words: “me”, “you”, “seek”, and “help.” Across language people will always be “seeking” something and will always have the concept of “helping”, indicating that it is simply human nature to do so. Most will also have a glyph for “death” or “make.” The message of that is clear: death is an inevitability, but so is creation. While their languages are different at their core, the groups are all people.

The story of the tower is one of how language can be used to divide us. The anchorites that founded the tower sit at the top, plugged into VR headsets and controlled by Exile. Without them connecting the other groups, the groups remain isolated from each other. It is only when you, the main character, take the time to translate between the groups and facilitate communication that they open their gates and help each other. Once you have reached the top and discovered Exile’s authoritarian control, you can move towards the true ending and shut it down. To do so, you have to travel back through the tower and free anchorites from Exile’s control and they will talk to the various groups. In the end, you can eventually free the whole tower from Exile and see people from all of the groups all at the top, freely mingling.

The lesson is ultimately that even if we can’t understand each other, we must still make the effort to do so because when we are divided it allows higher powers to take advantage of our division.

Note: The title was inaccurately misrepresented with “Senaar” in the print edition, this has been rectified in the online edition.